What’s in That Snack? Yuka Tells You—Because the U.S. Won’t

How one app is doing what federal nutrition guidelines won’t: exposing ultra-processed foods and empowering smarter choices.

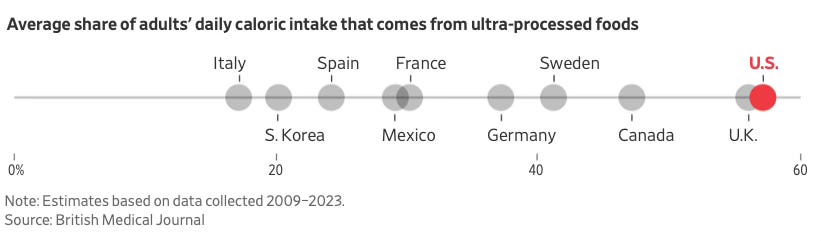

It has always been frustrating to me that the United States lacks a standardized rating system to identify and rank ultra-processed foods (UPFs), unlike countries such as those in the European Union, Brazil, and Mexico, which employ front-of-package labeling (e.g., traffic light systems, warning labels) or the NOVA classification to inform consumers about processing levels. While the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans mention limiting processed meats, they do not explicitly address UPFs as a distinct category linked to health risks, despite evidence associating UPFs with obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. This regulatory gap leaves consumers unaware of the degree of processing in foods, contributing to diets where UPFs account for over 57% of caloric intake. In contrast, countries like Chile and Brazil mandate clear labeling and restrict UPFs in public institutions, correlating with improved dietary choices. The absence of such measures in the U.S. likely exacerbates chronic disease rates, as unchecked marketing and accessibility of UPFs-engineered for hyper-palatability and linked to overconsumption persist without public health countermeasures. This heavy reliance on UPFs—high in sugars, unhealthy fats, and additives—contributes substantially to the nation’s high rates of chronic disease as indicated in this BMJ meta-analysis.

Enter mobile apps such as Yuka, that is rapidly gaining popularity by empowering consumers to make healthier choices about food, cosmetics, and wellness products. Launched in France in 2017, Yuka allows users to scan product barcodes and instantly receive a health score, accompanied by a simple color-coded system and detailed ingredient breakdowns. The app’s database now covers millions of products, and its user base has soared to over 65 million across 12 countries, with particularly strong adoption among Gen-Z and millennial shoppers in the United States and Europe. Yuka’s appeal lies in its straightforward interface, transparency, and independence: it claims that it is funded solely by user subscriptions, not by brands, and its scoring algorithm draws on scientific studies and regulatory sources like the FDA and WHO.

Let’s take a look at how some popular foods actually stack up—and the results aren’t pretty. Ritz Crackers and Ramen Noodles both score a 0/100, Cinnamon Toast Crunch comes in at just 8/100, Cheetos at 1/100, Pop-Tarts at 3/100, and even Diet Coke only manages a 41/100. As you can see, the low scores come with a clear explanation—additives are almost always the main culprit.

Now for some better news on the food front. It’s no shock that a vegetable medley and plain nonfat Greek yogurt earned stellar scores—100 and 94, respectively. But it’s especially satisfying to see personal favorites like hummus (75) and guacamole (69) fare well too, escaping Yuka’s harsher judgment. Interestingly, not all Greek yogurts make the grade—flavored varieties like Chobani’s Peach Cobbler scored much lower (45), weighed down by a heavy load of additives.

How does Yuka’s Point Scoring Work?

Yuka evaluates food and cosmetic products using distinct methodologies, combining nutritional quality, additive content, and organic certification (for food) or ingredient safety (for cosmetics). Yuka’s food scoring system rates products on a 0–100 scale using three main criteria:

Nutritional quality (60%): Based on the European Nutri-Score system, which grades foods from A (best) to E (worst). Foods high in calories, sugar, saturated fats, and sodium lose points, while those rich in fiber, protein, fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts gain points. Yuka’s scale roughly converts Nutri-Scores as follows: A → 100–75, B → 74.9–55 C → 54.9–35, D → 34.9–10, and E → 9.9–0. Products rated D or E cannot score above 49 to prevent overrating unhealthy items.

Additives (30%): Each additive is classified as risk-free (green), low risk (yellow), moderate risk (orange), or hazardous (red). The more additives—and the riskier they are—the greater the score reduction. Products with moderate-risk additives are capped at 50 points, while those with hazardous additives are limited to a maximum of 25.

Organic certification (10% bonus): Organic products earn a 10-point bonus. Non-organic items are scored without this boost.

Cosmetic scores (0–100) are based on the safety of a product’s ingredients. Each ingredient is rated as risk-free (green), low risk (yellow), moderate risk (orange), or hazardous (red). The overall score is primarily determined by the highest-risk ingredient: products with hazardous ingredients are capped at 25, while those with moderate-risk ingredients can score up to 50. Ingredients with lower risk levels help determine the exact score within these limits. Other key features include a database of 5 million+ products (3 million foods, 2 million cosmetics), independence from brand influence, and alternative product recommendations for low-scoring items.

Yuka’s Limitations

However, Yuka is not without limitations. One of the most frequent criticisms of Yuka revolves around inconsistencies in its database and scoring algorithms. The app relies on crowdsourced data and manufacturer-provided information, which can lead to errors in product evaluations. For instance, users have reported discrepancies in scores for identical products, such as two soy sauces with the same ingredients receiving different ratings due to database inaccuracies. These errors undermine trust, particularly when users encounter implausible results, such as non-vegan products incorrectly labeled as “vegan”.

Yuka’s scoring system applies a one-size-fits-all approach, which fails to account for individual dietary needs or health goals. For example, the app penalizes products high in saturated fats or salt without considering their role in balanced diets or specific cultural cuisines. The app’s reliance on the Nutri-Score system - a nutritional profiling tool focused on calories, sugars, and saturated fats - has also drawn criticism for oversimplifying complex dietary choices. Yuka also may penalize products with safe additives used in minimal quantities. Some users have also reported technical glitches, particularly with the app’s offline mode, which remains unreliable even for premium subscribers. Yuka acknowledges that its data cannot guarantee absolute accuracy, as product formulations may change without updates to the app’s database. Additionally, Yuka’s database, while extensive, is not exhaustive, and missing products or barcode issues can frustrate users.

Yuka is a good first start. It is good news for consumers if as reported, some manufacturers are reformulating their products in response to lower Yuka scores. As long as Yuka continues to be transparent and not materially profit from any relationship with Big Food, I am happy.

Takeaway: The United States lacks clear labeling or standardized tools to help consumers identify ultra-processed foods (UPFs), which now make up over half of Americans' diets and are strongly linked to chronic disease. In the absence of federal action, Yuka has stepped in —scanning barcodes to reveal nutrition scores, risks of additives, and ingredient safety. While not perfect, Yuka empowers healthier choices and is already influencing food companies to reformulate. It’s a promising workaround in a country where food policy continues to lag behind science.

I was not aware of Yuka so learned something alright! Setting aside privacy and other regulatory issues, what would be great is ability to capture actual behavior of users and perhaps some additional health metrics for those who use it regularly. In the long run, this could provide for some good data at least from a hypothesis testing perspective that can be followed upon by researchers.