Beyond the A1c: Unveiling the Hidden Dangers of Glucose Rollercoasters

Why Glucose Variability Matters More Than You Think for Your Heart Health and Longevity

If we are being health-conscious, we might dutifully get our fasting glucose and A1c levels checked once a year. But here’s the buzzkill: measuring average glucose levels isn't as helpful as we thought. A more meaningful metric is Glucose Variability (GV), but unfortunately, it is not reported in your standard metabolic panel.

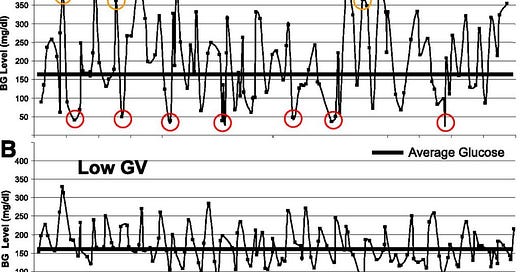

GV is an important predictor of health even more so than your average glucose or A1c. A “good” A1c number might look ‘good on paper’ yet masks frequent episodes of hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) or hyperglycemia (high blood sugar), shown by red and yellow circles respectively in the figure. Subject 1’s GV is quite high while Subject 2 has the same A1c = 8.0% but much less variability and minimal peaks and troughs.

What is Insulin Resistance?

Firstly, some basics. Glucose, the body's main energy source, comes from the food we eat and is regulated by insulin in a process called blood glucose homeostasis. After meals, blood glucose levels rise, and the pancreas releases insulin, which helps cells absorb glucose for energy or storage. High-carbohydrate meals, especially those with simple sugars, cause sharp glucose spikes, while meals with complex carbs, fiber, protein, and healthy fats lead to a slower rise. Exercise improves glucose control by increasing muscle uptake of glucose, lowering and stabilizing blood glucose levels. This also enhances insulin sensitivity, meaning cells use glucose more efficiently, resulting in better glucose control and a more stable glucose curve throughout the day.

Insulin resistance occurs when the body's cells, particularly in the muscles and liver, don't respond effectively to insulin, leading to elevated blood glucose levels. It is a precursor to prediabetes, type 2 diabetes, and a key factor in metabolic syndrome, increasing the risk of heart disease, stroke, and diabetes. As insulin resistance progresses, the pancreas struggles to maintain normal blood sugar levels. It is also associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and systemic inflammation, which can contribute to conditions like cancer and Alzheimer's disease. In fact, Robert Lustig argues in Metabolical that metabolic dysfunction (insulin resistance), rather than obesity itself, is the primary driver of chronic diseases like cancer, Alzheimer's, cardiovascular disease, and depression.

Glucose Peaks Increase Cardiovascular Risk

Based on the available scientific evidence, spikes in blood sugar and insulin levels appear to be more damaging than a more uniform increase. Studies suggest that postprandial1 spikes of high glucose levels may be a more robust determinant of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk compared to average glucose levels or A1c. This indicates that the fluctuations in blood glucose are particularly harmful.

A study using a mouse model of "transient intermittent hyperglycemia" found that exposure to postprandial glucose spikes just once a week accelerated atherosclerosis. The transient rises in blood glucose were found to activate circulating neutrophils2 through glycolysis3 and oxidative stress. This acute activation of inflammatory processes during glucose spikes may contribute to long-term vascular damage. Research also indicates that glucose variability, rather than just average glucose levels, is an important factor in diabetes complications. High glucose variability has been associated with increased oxidative stress4, which can lead to endothelial dysfunction5 and cardiovascular complications.

A Stanford study using continuous glucose monitoring revealed that even people considered "healthy" can experience significant glucose spikes after eating certain foods. These covert spikes may contribute to cardiovascular disease risk and insulin resistance, even in individuals without diagnosed diabetes.

This glucose curve pits a tablespoon of sugar against half a bottle of Coke, and guess what? Coke wins—with a higher peak! If this does not convince you to drop your sugary soda drinking habit, nothing can! Please, please avoid sodas like the plague.

To minimize glucose spikes and dips, it's important to focus on both food choices and the order in which you eat. Opt for non-starchy vegetables like broccoli and cauliflower, which are low in carbs and high in fiber, and include whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats like nuts, seeds, avocados, and olive oil. These foods tend to cause a slower, more gradual rise in blood sugar. Research shows that eating sequence also matters—starting with vegetables, then protein, and saving carbs for last can significantly lower post-meal glucose levels and require less insulin to process. The main point: eat your carbs last.

Based on these findings, some researchers argue that glucose-lowering strategies should focus more on reducing postprandial glucose spikes rather than just lowering average glucose or HbA1c. This approach may be more effective in reducing cardiovascular risk while avoiding the dangers of hypoglycemia associated with intensive glucose-lowering treatments.

Measure GV with a Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM)

If you are looking to get your own GV data, you're probably familiar with CGMs, which track your glucose in real-time and display colorful charts on smartphone apps. These devices can calculate metrics like Standard Deviation, Peak Values, and Time in Range. However, for those without diabetes, accessing a CGM can be tricky since insurance usually only covers them for diabetics. In many states, you will actually need a prescription to get a CGM, even if you are ready to pay out-of-pocket.

Peter Attia suggests that even non-diabetics should use CGMs to detect glycemic variability, which could indicate early stages of insulin resistance or impaired glucose tolerance, even in people considered metabolically healthy. CGMs can reveal abnormal glucose patterns that may indicate a pre-diabetic state before traditional tests can detect it. Additionally, they provide personalized insights into how diet, exercise, and other factors affect blood glucose, allowing for more tailored preventive strategies. However, while Attia strongly supports CGMs for non-diabetics, the broader scientific community (as is typical) has yet to reach a consensus on their benefits for this group.

In a subsequent post, I will document my experience with a CGM, including out-of-pocket costs and its utility.

Takeaway: To truly monitor metabolic health, average glucose levels like fasting glucose or A1c aren't enough. Glucose Variability (GV) provides better insights into risks like insulin resistance and cardiovascular issues. CGMs can reveal these patterns, but non-diabetics need to jump through hoops to get access to one.

Postprandial glucose refers to the concentration of glucose in the blood after consuming a meal or food.

Neutrophils are a type of white blood cells that act as your immune system’s first line of defense.

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that causes the breakdown of glucose by enzymes, releasing energy and pyruvic acid.

Oxidative stress is an imbalance of free radicals (bad) and antioxidants (good) in your body that leads to cell damage. It plays a role in many conditions like cancer, Alzheimer’s disease and heart disease. Toxins like pollution and cigarette smoke can cause oxidative stress, while foods rich in antioxidants can help reduce it.

Endothelial dysfunction affects your endothelium, which is the thin layer of cells that line the inside of blood vessels. Dysfunction means the cells cause your blood vessels to constrict or narrow, instead of keeping them open (dilated).

Thanks for the insightful post once again! Here are a few comments and counter points to start the discussion.

1. First, I fully agree that fasting glucose and A1c don't give you the full picture. Worse, they might even give you the wrong picture regarding your metabolic health. But, unfortunately, that's where we are in the health care system. My argument against A1c is that it is a lagging indicator of your glucose metabolism. You are always in reactive mode if you rely on A1c, rather than proactive.

2. I am a big proponent of proactive management of your health, so I don't think CGMs are helpful for those who are proactive. They are likely to throw you into a cycle of fear and food analysis-paralysis that is not very helpful or even healthy, IMO. That can cause more stress than it is worth.

3. Proactive health management requires eating healthy foods (which means whole foods), and that in itself is both necessary and sufficient as a guide. No further complications are necessary (based on my own experience and the advice of whole foods practitioners that I follow). For example, starchy vegetables are just fine (I eat a lot of sweet potatoes) as long as they are whole.

4. Regarding glucose peaks and CVD risk: If the primary goal is to regain insulin sensitivity in its true sense (i.e. not by controlling postprandial glucose levels for the same level of insulin production by the pancreas, but by reduced level of insulin production), then there is no reason to fear postprandial glucose spikes. The question is what is the definition of "frequent" in "frequent spikes"? Humans have eaten starchy vegetables for millennia (and still do in the blue zones and other native regions) without CVD. One big reason could be that they didn't eat all day. By spacing your meals (and not snacking in between), we can mimic the same. Your body is given a chance to lower glucose and insulin levels sufficiently before the next meal. I think this is where the case for fasting combined with whole foods becomes very strong.

5. Now, once you are diabetic, I fully agree that you need all the tools, including CGM, to take back control.