The Protein Dilemma: Red Meat’s Hidden Risks and Healthier Alternatives

How Moderating Red Meat Consumption and Choosing Healthier Protein Sources Can Boost Longevity and Well-Being

Adding more protein to diets has become a major health focus of late, driven by its multifaceted benefits for muscle maintenance, weight management, and metabolic health. For example, Peter Attia advocates for significantly higher protein intake—roughly 1g per lb. of body weight—to combat age-related muscle loss (sarcopenia) and maintain metabolic health. He emphasizes that muscle preservation is critical for longevity, as low muscle mass correlates with higher mortality risk. Attia argues that the standard RDA (0.4 g/lb.) is grossly insufficient, especially for active individuals or those over 50, where muscle retention becomes harder.

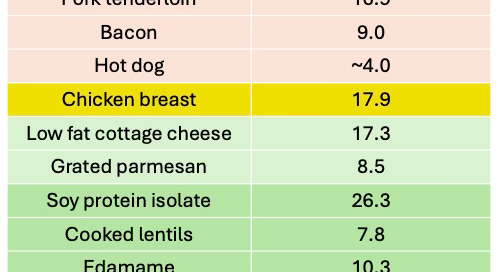

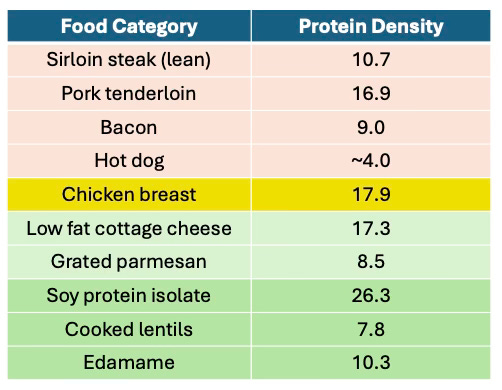

This raises the natural question: what should we eat to meet our daily protein needs? The table above shows the protein density1 of various food categories: red meat, chicken, cheese, and plant-based options. While it's commonly believed that red meat has the highest protein content, the protein density data suggests otherwise—it’s not the top choice when comparing these food categories.

Harvard Study Reveals the Health Risks of Red Meat Consumption

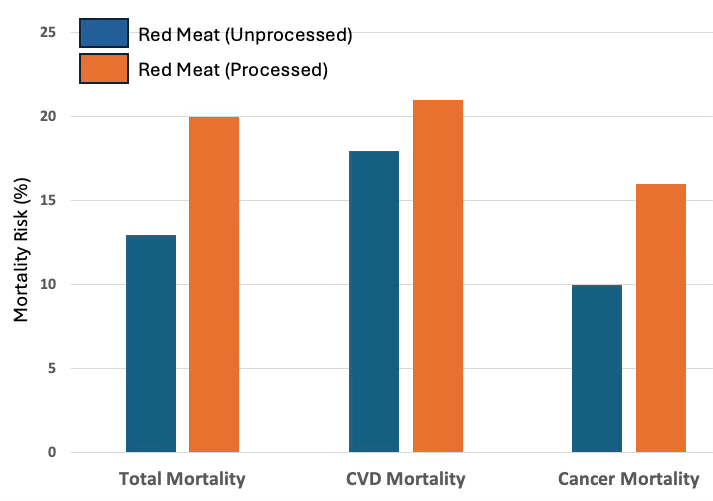

Back in the 80s, researchers at Harvard started following 120,000 people (37,000 men, 83,000 women), who were initially free of known heart disease and cancer. Meanwhile, all along, every four years, the researchers were checking in, and keeping track of everyone’s diet. A few decades later in 2012, about 24,000 had died, including about 6,000 from heart disease, and 9,000 from cancer. In 2012, results from these two major Harvard studies were published. What did they discover? The findings were clear: red meat consumption is linked to a higher risk of overall mortality, as well as increased mortality from cardiovascular disease and cancer—resulting in a significantly shorter lifespan. The accompanying chart highlights that processed red meats (such as cold cuts, sausages, and hot dogs) are even more harmful. Importantly, these conclusions hold true even after adjusting for factors like age, weight, alcohol consumption, exercise, smoking, family history, caloric intake, and the consumption of healthy plant-based foods like whole grains, fruits, and vegetables.

The 2012 Harvard study identified heme iron, saturated fat, sodium, nitrites/nitrates, and carcinogens formed during cooking as key contributors to the adverse health effects of red meat consumption. Heme iron (found abundantly in red meat) promotes oxidative stress and free radical production, damaging cells and DNA. This process is linked to inflammation, insulin resistance, and atherosclerosis, increasing risks of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer. Processed meats (e.g., bacon, hot dogs) contain sodium nitrite as a preservative. These compounds form carcinogens in the digestive tract, which are directly linked to colorectal cancer. In addition, excessive intake of sodium (present in processed meats) elevates blood pressure and CVD risk. To make matters worse, grilling or frying red meat produces heterocyclic amines (HCAs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are mutagenic and linked to cancers of the colon, pancreas, and prostate. As shown in the chart, processed meats exhibited 20% higher mortality risk per serving compared to unprocessed red meat (13% risk). This difference stems from the synergistic effects of additives (nitrites), higher sodium, and heme iron concentration. For example, nitrites in processed meats not only enhance carcinogen formation but also impair insulin response and vascular function.

IGF-1’s Role in Red Meat-Related Health Risks

There is a common pathway that is triggered by these unhealthy ingredients in red meat (processed and unprocessed). A 2014 study in Cell Metabolism identified this hormonal pathway — IGF-1 ( Insulin-like Growth Factor 1) as a critical mediator of red meat’s health risks.

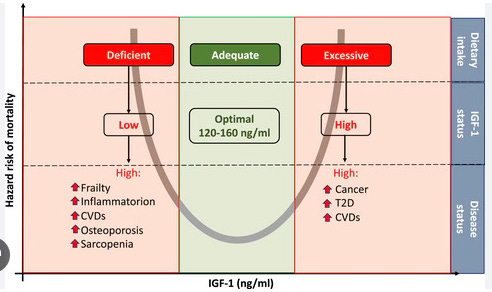

IGF-1 is essential for stimulating bone, muscle, and tissue growth in children, driving height gain and organ development during puberty. In young adults, it supports cell regeneration, muscle maintenance, and metabolic functions like glucose regulation. Deficiencies can lead to stunted growth or developmental delays, while balanced levels ensure proper physical maturation.

High intake of animal protein (especially red meat) stimulates IGF-1 production, a hormone that promotes cell growth and proliferation. Elevated IGF-1 levels are linked to increased risks of breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers, and increased insulin sensitivity leading to Type 2 diabetes. For every 10 ng/mL increase in IGF-1, cancer mortality risk increases 9% in adults aged 50–65. Processed meats (e.g., bacon, hot dogs) exacerbate this effect due to additives like nitrites, which may amplify IGF-1 signaling pathways. Studies show a U-shaped relationship (shown below) between IGF-1 levels and mortality: both low and high IGF-1 levels correlate with increased risks of death from cancer, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and all causes. In the context of red meat consumption, excessive animal protein intake pushes IGF-1 into the “high-risk” range, promoting tumor growth and metabolic dysfunction.

In summary, the researchers estimated that 9.3 percent of deaths in men and 7.6 percent in women could have been prevented at the end of the follow-up if all the participants had consumed less than 0.5 servings per day of red meat. They also concluded that replacing one serving of total red meat with one serving of a healthy protein source was associated with a lower mortality risk: 7 percent for fish, 14 percent for poultry, 19 percent for nuts, 10 percent for legumes and low-fat dairy products, and 14 percent for whole grains.

The bottom line is that reducing red meat consumption to no more than 1-2 servings per week can help extend your lifespan. To meet your daily protein needs, focusing on fish, poultry, and plant-based proteins like beans and lentils is a healthier choice. (Full Disclosure: I’m a vegetarian who includes dairy products like milk and cheese in my diet, but I don’t eat fish or poultry).

Takeaway: Increasing protein intake, especially for muscle preservation and metabolic health, is crucial, particularly for those over 50. However, red meat consumption, especially processed varieties, is linked to higher mortality risks owing to elevated IGF-1 levels, and healthier protein sources like fish, poultry, and plant-based options are better choices for long-term health.

Calculated as grams of protein per 100 calories.

I stopped eating red meat and poultry several years ago. Most of my diet is plant-based, but I do eat fish. I’ve found other protein sources, and just turning 79, I surprisingly discovered the people my age need more protein in their diet. One can of herring filets has 26 grams of protein, about half of required protein for my age, which I fill in with other sources like low-fat cottage cheese, nuts, nut butters, smoothies with pea protein powder, and beans. It can be done.

I have not eaten any meat for 25 years now and I very healthy for my age as I am told .

Meat is not the only thing that contains protein .

We were all lied to by the beef,poultry and pork corporations so they could make a profit

I have not consumed dairy in as many years .

Go plant based and save our environment